Ibn Khaldun Returns on a Path Not Taken

Do you think about paths not taken? Do you dream of being in a life where you made different choices - a life where you are swimming in the South Pacific, or still with your childhood sweetheart, or opening a none-person art show in Paris? Late in life Jung came to the conclusion that in dreams he was present in scenes of continuous life he was living somewhere else. I have had this impression for decades. Sometimes I check in - body and all – to a life that is radically different to my present one, sometimes it’s not so remote. For example, I may be in episodes in the life of a bestselling novelist who has won over the critics while expanding his popular audience with superior historical spy fiction. I was on that track until I started dreaming in the Mohawk language in the 1980s and had the experiences that led me to embark on a new life as a dream teacher. This parallel Robert travels to some of the countries where I led taught Active Dreaming workshops before the pandemic, with a different agenda and a much bigger budget. He pays attention to his dreams and they help him to shape his characters, to generate dialogue, and to fill in gaps in a plot. Maybe he dreams of being in my life.

I also dream of being in the situations and seemingly the bodies of personalities in past and future times, as many of us do. I have come to understand that the challenges and dramas of my present life are related to situations in other places and times involving other members of my multidimensional family. I write about this candidly in The Boy Who Died and Came Back. My experience and observation leads me to agree, with the Seth who spoke to us through Jane Roberts, that from a certain point of view it is all going on Now. We can reach backwards, forwards or sideways to make useful connections with these other selves.

In this essay I am not going to deal with past lives, future lives, or what happens between lives. I am going to tell a new story that involves the interaction of two parallel selves – mine – who have been following the same basic timeline in different life experiences. I will tell this story as simply and concisely as possible.

On Thursday, I was scheduled to teach an online class I had titled “If You Come to a Fork in the Road, Take It”. You probably recognize these words of advice; I borrowed them from Yogi Berra. The theme of my class was that we not only dream parallel lives; as active dreamers, we can seek to connect with a parallel self, observe its trajectory and maybe even exchange gifts and skillsets and resources. If the Many Worlds hypothesis in physics is correct - if the universe is constantly splitting and we have (as Braine Greene likes to say) endless doppelgangers in countless worlds - and this theory is supported by the content of our dreams, then why can’t we reach to a second self in their own continuum?

With or without our knowledge, it seems likely that we are constantly shadowed by our alternate selves. Our paths converge, for better or worse. We come to a place or person we recognize, though we have never seen them in our ordinary lives before. This is often because we dreamed this encounter, though we may have forgotten the dream. I suspect it is sometimes because an alternate self got here before us. When we are looking for evidence of the Many Worlds on our human scale, in addition to searching our journals for serial dreams we want to monitor cases of what is called déjà vu but might be better identified as déjà rêvé (already dreamed) or déjà vécu (already lived).

We can inherit karma, good or bad, resulting from the action of a parallel self in another time continuum. Awakening to these effects is shadow work that goes beyond the popular self-help strategies that are being offered under that rubric. With greater consciousness, and heightened understanding of the mobility of consciousness, we may be able to do good for ourselves and one or more alternate selves by seeking each other out and making a mutually beneficial exchange of gifts.

I am going to share a new story of conscious engagement with a parallel self, and of confirmation of the connection from the world. It is my personal story, and the details are highly specific and involve lines of scholarly research that may or may not be of interest to you in themselves. I hope that in at the least my story will expand your sense of what is possible in your own life.

On Thursday morning prior to my class, I drifted in that liminal state the Scots call hurkle-durkle before getting out of bed. I wondered what parallel timeline I might be drawn to follow when I led my class on a lucid dream journey to explore parallel lives with the help of shamanic drumming, which fuels and focuses expeditions of this kind. My mind wafted back to a scene from more than half a century ago. I was back at the Australian National University in Canberra, in the office of a research professor at the School of Advanced Studies. I had been awarded an amazing scholarship that would enable me to go to any university in the world and pursue any subject or specialty I liked on my way to earning my PhD. I did not know where I wanted to go or what book I most wanted to write – in those days, getting a PhD was essentially about writing a dissertation that could be published. To put it mildly, my interests were diverse. I had given a talk on Advaita Vedanta, and a lecture on Marshall McLuhan and was reading Rilke in German. I had published some poems and many leaders, book reviews and vast “pre-need” obituaries of world leaders for the Canberra Times. The latter assignment made me feel a bit like a crow, watching for the demise of a head of state or prime minister in order to see myself fill a page or two of print.

I had majored in history, and was happy to call myself a historian, though I preferred to call myself a poet.

Talk to Amir, my favorite professor advised. Amir was a brilliant Pakistani scholar recently arrived on campus. He asked about what I had learned in my historiography class, and the thesis I have written on French Existentialists in the time of the Algerian war. He asked what I knew about Ibn Khaldun. Very little, I confessed. A medieval Muslin historian. Oh yes, and more. A world historian. Born in Tunis from a family that dined with the caliph in Andalusia, he started writing a history of the Berbers. His project grew until, by the time he completed his book in Cairo, it had become a history of all things human. He depicted the human drama playing on six stages, like economics and geography. One of the stages for the play of history, he explained, is dreams and visions. Ibn Khaldun maintained that we cannot understand the real order of events without reaching from the visible into the invisible, as people do when they dream and interact with the beings they encounter in realms of true imagination. He is perhaps the only world historian who has taken this view.

The Pakistani professor suggested that Ibn Khaldun, the man and his work, might be good topic for a dissertation. He loaned me a commentary on the Muqaddimah, Ibn Khaldun’s three-volume introduction to his world history, which he called the Kitab al-Ibar, the Book of Lessons or better, The Book of Admonitions. The title suggests, unsubtly, that we must learn from the past in order to navigate the present and shape the future.

I was sufficiently hooked to start learning Arabic – though my partner at that time complained that I sounded like I was constantly gargling and clearing my throat – and bright home armfuls of books from the university library. Then I moved on. I don’t recall clearly why I made that choice. Maybe I was unconfident about my Arabic.

Anyway, as I looked back over my earlier life, still between the sheets in the dawn light, I recognized that my decision not to go with Ibn Khaldun was one of the decisive turning-points in my life. I had come to a crossroads with clear signage, and had chosen which way to turn. In reverie, I now had a strong vision of what my life might be had I written the book on Ibn Khaldun. I would have become a professor, respected in his field, with a long list of specialist publications and a few books written for popular audiences and perhaps a few historical novels and a series for The History Channel. On the path not taken, I became a respected academic with a slew of books for specialists, a few for popular audiences as well, and at least one historical novel of the Ottoman empire. The professor is fluent in Arabic, Turkish, Farsi and other languages. He is much ion demand as a lecturer, speaking at great universities all over the world map. He does not lead dream workshops, but he records his own dreams and shares them privately. His books show how dreaming has been a secret engine in the whole human odyssey on the planet, which is the theme of my book The Secret History of Dreaming.

I get out of bed and tap “Ibn Khaldun dreams” in the Google search box. Half the screen is suddenly filled by the bright bronze face of a bearded man in a turban. I am looking at a life-size portrait bust of Ibn Khaldun. I glance at the credit line. The statue was commissioned by the National Arab American Museum. The sculptor, Patrick Morelli, lives in Albany, New York. My town. I have lived here for more than twenty years. I am slightly stunned by the loop that has just been made from Australian to Albany. I was introduced to Ibn Khaldun in my native Australia over fifty years ago. He is looking at me now, thanks to a neighbor in my new hometown. The world historian who was drawn to dreams returns to the world dreamer* who was drawn to history along a path not taken.

In fact the path was taken by a parallel self and is now converging with my present continuum in what one of my dream acquaintances calls mortal life. I feel the nearness of the professor in my energy field. This gives me a welcome sense of solidity as I continue my fervid research, writing and editing for new essays and books that involve the history of dream experience, not least in the Islamic world and the Ottoman empire.

I pluck a line from Ibn Khaldun as my banner for the day:

“Everyone is successful at the things for which he was created.”

*I teach courses in Active Dreaming for students from Senegal to Seattle to Sydney. As an independent scholar, I study how people dream. what they do with their dreams, where their derams take them and what they bring from dreams into mortal life, in every culture and tradition I can track.

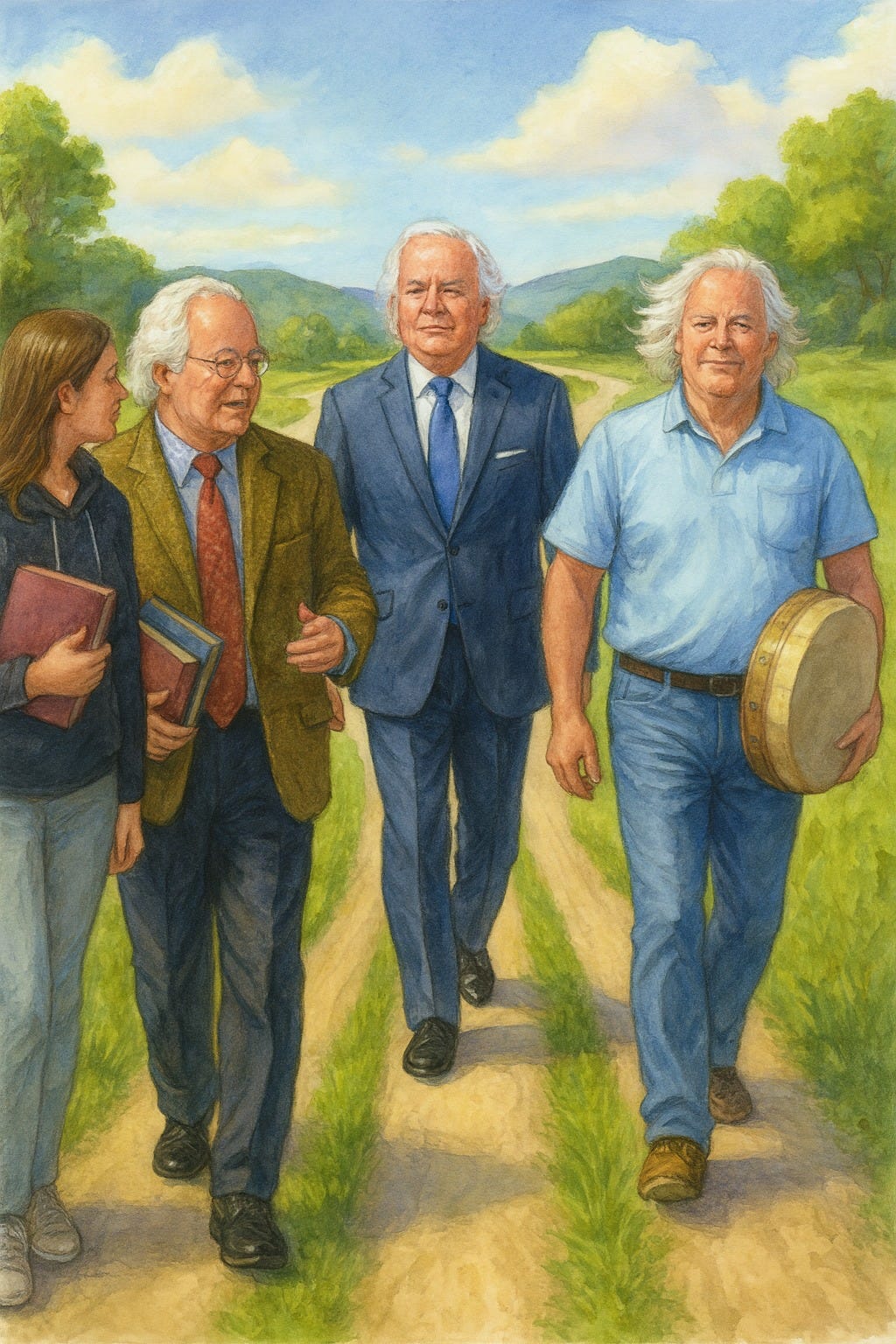

Illustration: Three Paths. I encouraged AI not to be flattering. The figure on the left. talking to a student, is Robert the professor. The well-fed suit bringing up the rear is Robert the businessman; he still does not understand why I turned away from fame and moneypots to follow the path of a dream teacher. The figure with drum is of course the Robert who leads adventures in shamanic dreaming.